FOR MOST, RETIREMENT COMES AS A WELCOME REPRIEVE–a chance to stop working, stop moving, stop planning. For Dave McCoy, the man who sculpted Mammoth Mountain Ski Resort, there has been no such pause. McCoy will celebrate his 100th birthday on August 24, yet another milestone that would permit a man to clock out, but he’s not interested. After McCoy opened the first chairlift at Mammoth on Thanksgiving Day, 1955, he spent five decades–never once taking a vacation–making his mountain a great place to ski. Though he sold the resort in 2005, marking an end to his 50-year tenure that resulted in 38 chairlifts and more than 4,000 acres of skiable terrain, McCoy hardly called it quits.

“Dave really wrote the book on contemporary California ski areas. He was always looking for ways to do things differently,” says Michael Berry, president of the National Ski Areas Association. “He’s an operational genius, a creative force. He set the standard for the whole industry.”

His hobby now is taking photos of the wildflowers, mountains, rocks, and trees that surround his home in the Eastern Sierra. McCoy has turned an interest in digital photography into a photography business run at his ranch near Bishop, about 40 miles south of Mammoth, with the help of his assistant Brandon Russell. He skied and rode motorcycles until he had his knees replaced in 2008 and now accesses wilderness terrain in a customized Rhino ATV. He tinkers with it constantly, even converting one to an electric vehicle, to keep his mind fresh.

“He’s an operational genius, a creative force. He set the standard for the whole industry.”

–Michael Berry, president of the NSAA

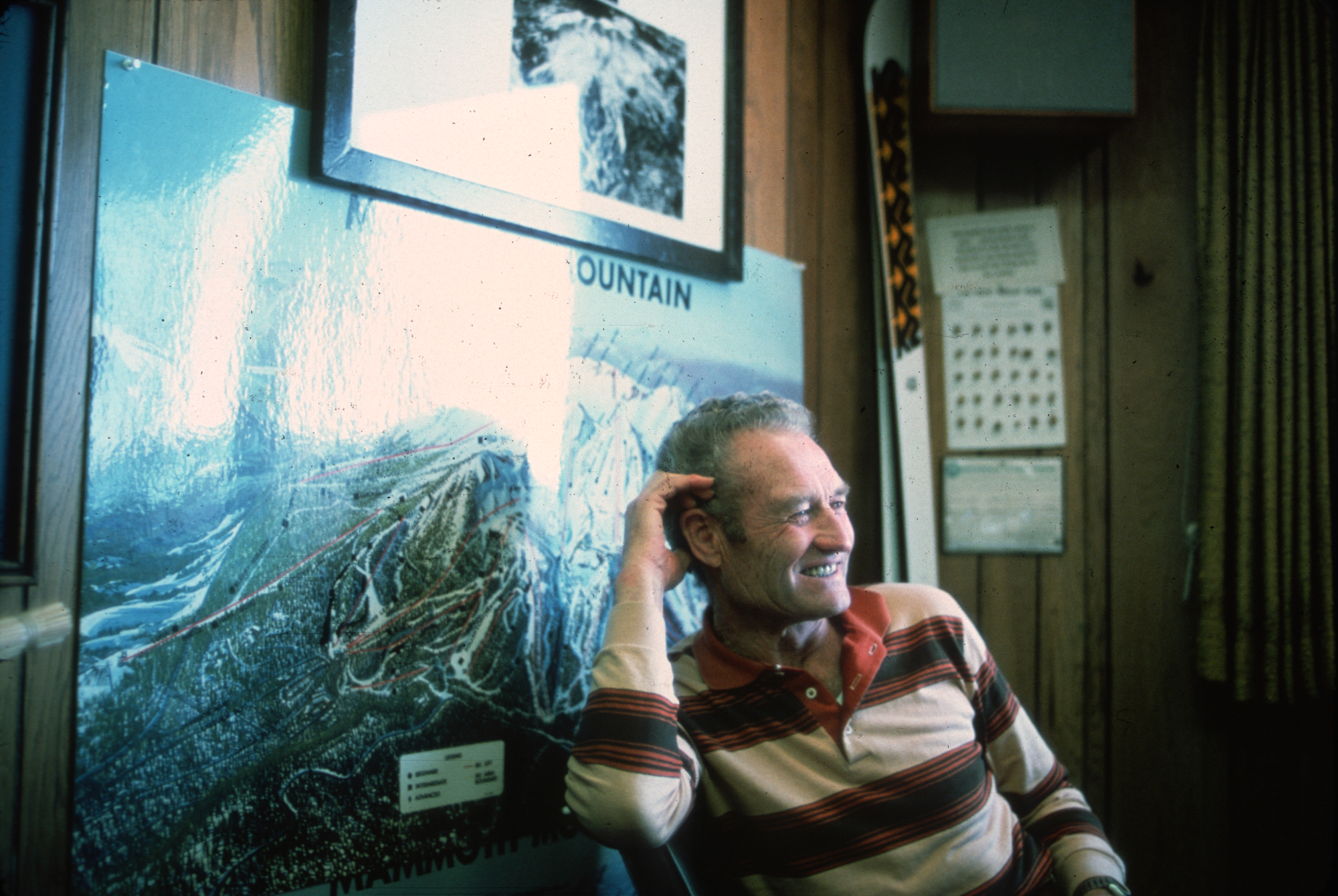

It was 1937 when McCoy started the project that would become the largest ski resort in Central California. He was 22 years old, classically handsome with a square jawline–always clean shaven–and rippling dark blond hair pushed back from his forehead. His skin was tanned from days spent on the mountain. Tall with broad shoulders, McCoy had been offered a number of scholarships to play college football, but he turned them down. He wanted to ski.

Even while he was building the resort from the ground up, McCoy was always skiing. He was headed toward the 1940 Olympics in Japan but because of World War II, no Olympic Games were held that year. Instead, McCoy looked to the next generation of ski racers, including two of his six children, and coached 14 skiers on their way to their own Olympic moments.

“Being coached by Dave was amazing. It was like a fairyland,” says Robin Morning, who ski raced for Mammoth Mountain before competing on the U.S. National Team from 1965 to 1968. “As a coach and as a person, he doesn’t talk much. He listens. He’s always upbeat and he absolutely loves skiing. That love came out in his coaching. Everyone wanted to be part of his team. If you paid attention and gave your best, he didn’t care about your ability level. He just wanted to help you ski.”

As Morning recounts in her book, Tracks of Passion, McCoy transformed a non-existent mountain town and built an empire around his great love for skiing down mountains. But his love and commitment to the Eastern Sierra went beyond the ski hill as well, as he helped start the hospital, fire department, and schools in Mammoth Lakes. In 1989 he launched the Mammoth Lakes Foundation to bring higher education and the arts to the Eastern Sierra. Six hundred scholarships, covering tuition and books, have been awarded to local students since 2003. McCoy is quick to deflect credit for it all to the employees, friends, and community who have stood by him.

“I’m proud of what we did and proud of how we did it,” says McCoy. “I say ‘we,’ because that’s what it was.”

MCCOY STARTED SKIING IN WASHINGTON WHEN WAS 13–a lucky number, he says. Despite the hardship of the Great Depression, the invention of the rope tow, T-bar, and chairlift brought a steady incline of skiers to the mountains. Leather boots and steel-edged wooden skis sold at department stores enabled, for the first time, controlled turns on hard snow and ice. McCoy made his own skis: long wooden boards he carved from ash.

“Now there’s a different ski for every day, every turn, every run. That doesn’t fit me. I just want one ski to go all over. That’s all. I just love to ski.”

–Dave McCoy

“We didn’t know there would ever be anything better,” he says. “Now there’s a different ski for every day, every turn, every run. That doesn’t fit me. I just want one ski to go all over. That’s all. I just love to ski.”

Born in El Segundo, California, McCoy grew up on the road. His father was in the paving business, helping to build some of California’s main highways, and moving the family with him. They stayed in tent camps with hobos and travelers along the way until McCoy went to live with his grandparents in the state of Washington.

In 1928, McCoy and his mother visited friends in Independence, California, which sits on Highway 395 between the Mojave Desert and the high peaks of the Eastern Sierra. McCoy instantly knew he would make a life in those mountains. He spent the next few years hitching back and forth from Washington to California, waiting for his chance to make the Sierras his permanent home. “I rode with the bums on the trains, ate at their campfires at night, and listened to their stories. That was my education,” he says.

After finishing high school in Washington, he hitched his way back to Independence where he got a job at restaurant waiting tables and washing dishes. It was there he met his future wife, Roma, a cheerleader who caught McCoy’s eye when she dropped by the restaurant. Roma, too, is as strong and determined as she is generous–for 73 years she has shared her husband with Mammoth Mountain, its employees, and a community of skiers who also love him.

When the two met, the nearby area around McGee Mountain and Mammoth had a population of six people. Storms that could drop as much as 20 feet of snow and winding roads kept most away–but McCoy, who worked as a hydrographer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, had intimate knowledge of the area. The job paid just $4 a day, but it meant he could spend his time outdoors, sometimes skiing as far as 50 miles a day, checking water and snow levels throughout the area. Though the mountains were remote, he saw them for what they were: a great place to ski.

When he asked the local bank for a loan of $85 to help him build a rope tow using the axle of a Model A Ford, he was turned down. But Roma, who then worked as a secretary at the bank, convinced the bank manager to grant her future husband the loan. After installing the tow, McCoy charged 50 cents a day to ride it. He wasn’t worried about the next day, only the day at hand–only the next run down the mountain.

RECORD HIGH SNOWFALL WAS BECKONING MORE AND MORE SKIERS from Los Angeles and nearby areas to make the trek to Mammoth. The Forest Service took notice, asking for bids to develop Mammoth into a ski area. McCoy made his pitch. The only pitch. “I took a piece of paper and drew three lines, which were for chairlifts. That was the business plan,” he says. “The only reason I got it was because no one else wanted it.”

Without a college education or formal training in business or engineering, McCoy spent the next 60 years growing Mammoth. For millions of skiers, it was the place to ski. For thousands of employees, it was the place to work. McCoy was doing the impossible and people wanted to be part of it. They wanted to be near the man leading the charge, the man motivated by the chance to ski.

“I know how I did it, and how it treated me. The corporate structure is so different. They make money. I made fun.” –Dave McCoy.

John Armstrong came to work for McCoy in 1971, fresh out of high school, and remembers McCoy as someone with a unique ability to size someone up. Which is why he required all of his male employees to adhere to a strict grooming code: sideburns no longer than the bottom of the ear, hair no longer than the collar, and no facial hair. “One thing that Dave found during the Great Depression, the people who never gave up hope were the people who take care of themselves–cut their hair, washed their clothes–and that always impressed him,” says Armstrong.

McCoy’s approach was unconventional. His bottom line was never about the money, it was about people–and finding new ways to get them skiing down the mountain, he says. He once told the Los Angeles Times, skiing had been so good to him at Mammoth, he couldn’t help but to return it to the skiers and see that they had a better place to ski.

“I know how I did it, and how it treated me. The corporate structure is so different. They make money. I made fun,” says McCoy.

This is a man who knows how to have fun. A shirtless Dave McCoy could often been seen on the mountain in the ’30s and ’40s. PHOTO: Mammoth Mountain Ski Area

Hub Zemke, who founded Hexel Skis in a space provided by McCoy, says the man is one of a kind–a cowboy who believes there is always a way to make a good idea happen. “There’s nobody like McCoy in the ski world in the United States,” says Zemke. “Dave came out of the Great Depression into the romantic era of skiing. Today, that’s gone. Passion is gone. But he pioneered it and literally did it at the end of a shovel.”

Selling the resort for $335 million 10 years ago is not something he likes to talk about. He skims over most inquiries about the past, talking in sweeping and abstract sentences about such iconic times. It seems he remembers telling his stories about the ‘back when’ more than he recalls the events themselves. At 100 years young, McCoy is, as he always has been, focused on the present moment.

“Life is just what you make of what falls in your lap,” he says. “Be happy, make the day happy. It’s all in your attitude, the way you open your eyes in the morning. You got to jump up and go do something.”