In an ideal world, you’d only be eating foods that lack labels. “Foods that don’t have labels are often some of the best things you can eat–the fresh fruits, vegetables, and herbs from the farmers’ market; the fresh seafood at the fish market; and the amazing whole-grain bread from the local bakery,” says Susan Bowerman, RDN, coauthor of What Color is Your Diet?. But let’s face it: Most of us still rely on packaged foods pretty heavily, and even if you’re managing to keep them to a minimum, the occasional granola bar or frozen dinner can come in handy.

That’s not necessarily a problem, provided you choose carefully. The key, of course, is reading some fine print. “Food labels are important tools that empower consumers to make smart choices,” says Jennifer Glockner, RDN, creator of Teddy Tries a Veggie, a nutrition e-book for kids. (Something you don’t have to ponder? The incredible benefits of Prevention’s new Younger In 8 Weeks plan–women lost up to 25 pounds in just 2 months.)

Even if you’re already in the habit of scanning labels, you’re unlikely to spend more than a few seconds studying one before tossing an item in your shopping cart–and we’re betting your eye immediately goes to a few details and then you ignore the others. That’s fair enough, but are you homing in on the right info? We asked registered dieticians to share the top four things they look for on food labels to help you make healthier selections fast.

1. Added sugar

Most dietitians agree that lots of added sugar is a big no-no. “Many pre-packaged items contain added sugars for extra flavor, extended shelf life, and as a fat replacer,” says Gisela Bouvier, RDN. While you probably won’t be surprised to find these in candy, cookies, and soft drinks, added sugar can also be lurking in your spaghetti sauce, “protein” bars, and condiments like ketchup and barbeque sauce. (Here are some other suprising sugar bombs you should be aware of.)

“Excess sugar in the diet can lead to weight gain and increase your risk for diabetes and heart disease,” says Bouvier. She notes that research has found that 1 in 10 people get 25% of their daily calories from added sugar–and that those in the heavy sugar camp are more than twice as likely to die prematurely from heart disease compared to those who limit their added sugar intake to less than 10% of total calories.

Figuring out just how much added sugar is OK can be a bit confusing, but the American Heart Association offers a good guideline: No more than half of your daily discretionary calories (i.e. treats) should come from sugar. For most American women, that translates to about 100 calories per day, or 6 teaspoons of sugar; for men, it’s 150 calories or 9 teaspoons.

At the moment, you won’t actually find added sugar listed on a food label. You’ll only see total grams of sugar, which includes the kind that’s naturally found in some items like fruit. That’s changing, thanks to a new FDA rule, which will largely go into effect in 2017. In the meantime, you should pay attention to total grams of sugar and also examine the ingredients list. And remember, added sugars go by many different names: “Watch out for various forms including dextrose, corn syrup, honey, cane crystals, maltose, sucrose, and fructose,” says Bouvier.

2. Trans fats

These have been newsworthy in recent years, and for good reason. Partially hydrogenated oils, aka trans fats, “are the worst type of fat you can consume because they raise LDL (bad) cholesterol and lower HDL (good) cholesterol,” says Bouvier. They raise your risk of developing heart disease and stroke, and they’re also linked to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

While some manufacturers have phased them out, Adrienne Youdim, MD, the director of the Center for Weight Loss and Nutrition in Beverly Hills, warns that trans fats are still found in many packaged snacks and baked goods. Ideally, your intake of these should be zero, but you should know that it’s possible to see “0 grams” on a label even when a food still contains a small amount. That’s why it’s also worth reading the ingredients list; if you see “partially hydrogenated oils,” it’s safest to pass.

3. Saturated fat

Unlike trans fats, you need some saturated fat–but you don’t need a lot. And while a few recent studies have suggested that saturated fat has been unfairly demonized, most nutrition experts maintain that less is better. “Less than 10% of your total calories should come from saturated fat,” says Lisa Dierks, RDN, wellness dietitian manager at the Mayo Clinic Healthy Living Program in Rochester, Minnesota. “Saturated fats should be replaced with mono or polyunsaturated fats, which help to lower LDL cholesterol levels and reduce incidence of cardiac events.”

4. Sodium

High intake can lead to hypertension, which is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney disease. And even if you rarely pick up a salt shaker, you’re probably getting too much. “About 70% of the sodium most of us get comes from processed food,” says Glockner. “The current Dietary Guidelines recommend that healthy adults should limit sodium intake to 2,300 mg–or about one teaspoon of salt–per day.”

The biggest culprits tend to be savory snack items and soups, says Noni Vaughn-Pollard, a registered nutrition and dietetics technician who works with the Foodstand app.

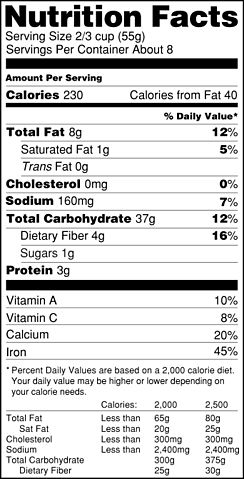

Checking sodium content on food labels is crucial–but so is paying attention to serving sizes. “Too often people read the Nutrition Facts without realizing that the information is based on the serving size listed at the top of the label,” says Stephanie Dunne, RDN, an integrative and functional nutrition specialist in New York City. A can of soup, for instance, might say that it contains 33% of of the Daily Value for sodium, which doesn’t sound so bad. The problem, of course, is that most of us eat the entire can without realizing that it contains two servings. You need to multiply the sodium (or fat or sugar) content by the number of servings you’re actually going to eat, says Dunne.